Designing Pipeline Tools for Maya

This post will be using my current autorig work as an example for my general approach to larger tools for Maya.

Compared to my previous attempts at a sustainable autorig system, my current iteration has inspired me to be much more conscientious of a pipeline tool’s identity as extendable software. In 3D production, where project goals can vary vastly between products, it is important to build tools for longevity and ease of use.

My approach for autorigging has always been to think of a rigged creature as modular, made up of abstracted body parts and systems. Modularity is the foundation for preparing any tool or asset to be reusable. For this project, I have been mindful in designing the software to be easy to iterate by both the artist and programmer.

First, let’s look at some Python-specific design techniques that have helped with this goal.

Classes and Separation of Responsibility

It is well understood the benefit of code reusability that comes with leveraging inheritance with Python. I like using classes, but I want to be careful and specific about what I define as a class. For the autorig I’m (loosely) setting a rule that my classes should only have one direct subclass, with any extra features being handled with composition instead.

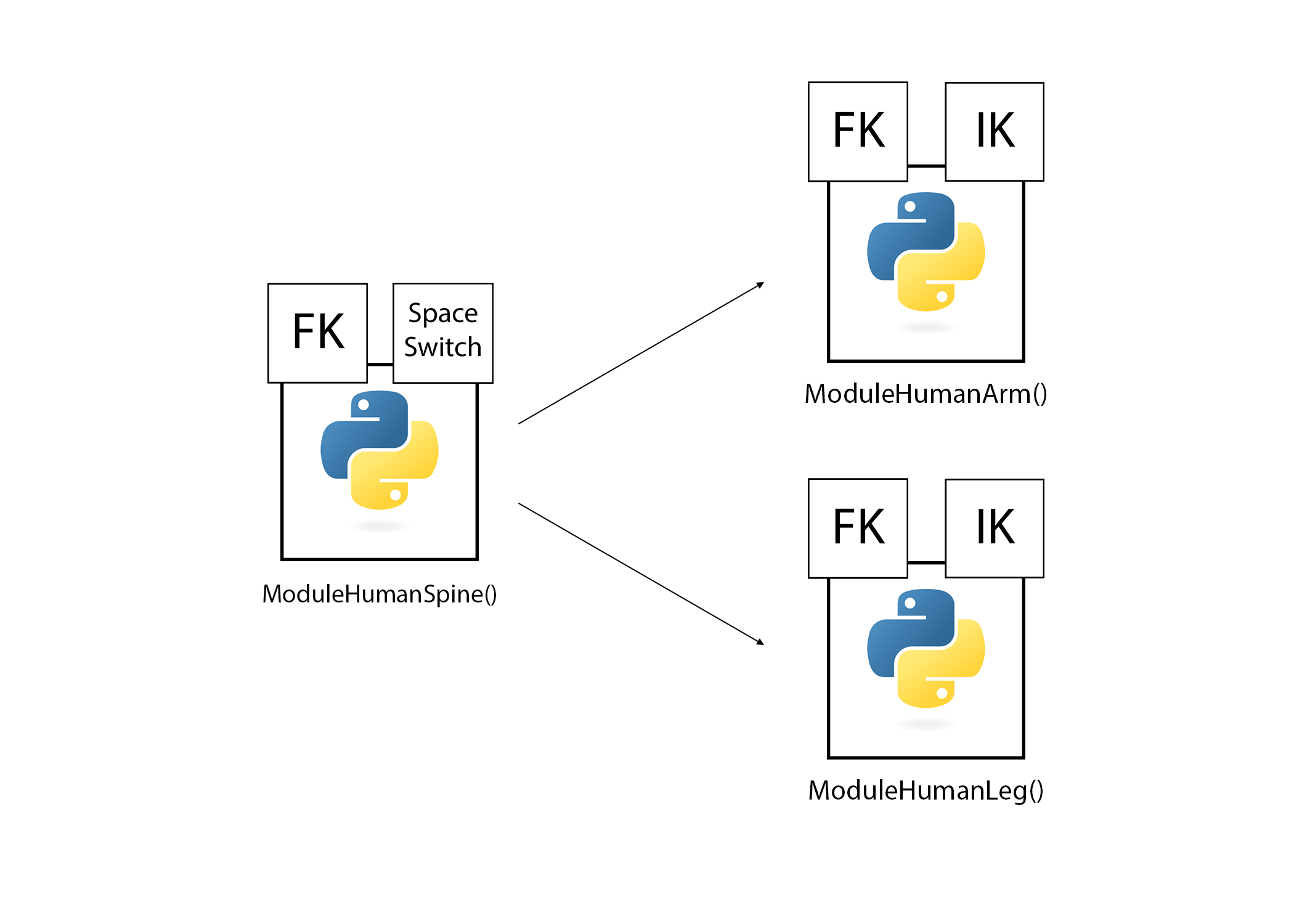

Each module in my rig, such as HumanSpine, share a common ancestor with the ModuleBase class. Through composition, classes representing key rig features like FK and IK are instanced and implemented. By separating the module containers from the node specific logic, it becomes easier to make adding and subtracting these systems bi-directional.

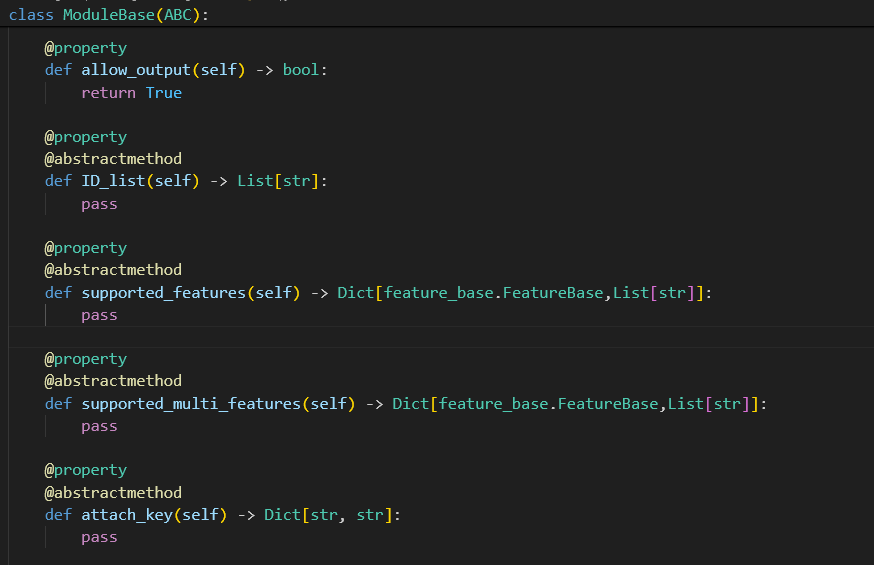

In a GDC talk given by Muhammad Bin Tahir Mir, he speaks on the importance of using techniques like abstract class methods and properties to keep the structure and design of your code consistent between tools. This makes it so you or your team has a common design pattern as a jumping off point for new code.

For example, my module classes have the abstract property “ID_list.” This is a list of strings that define what bind joints are in the module. If a module wants to use FK, it can just pass the ID list to the FK() class, without having to have the specific cmds logic in the module class.

Adding New Systems

Using inheritance while being mindful of keeping a small parent-child hierarchy makes it much easier to add further functionality down the road, especially if a new developer is brought on to the team.

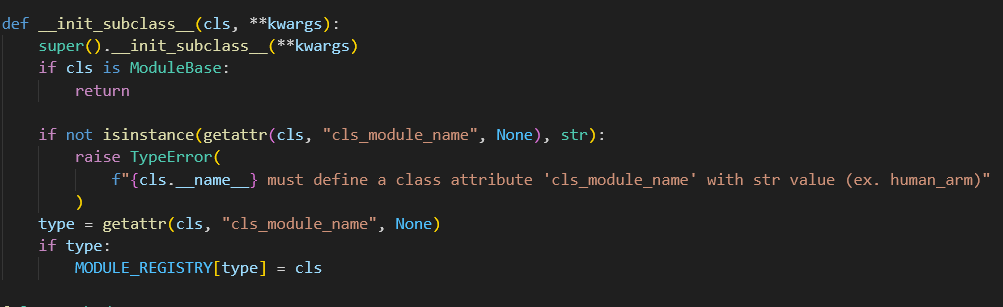

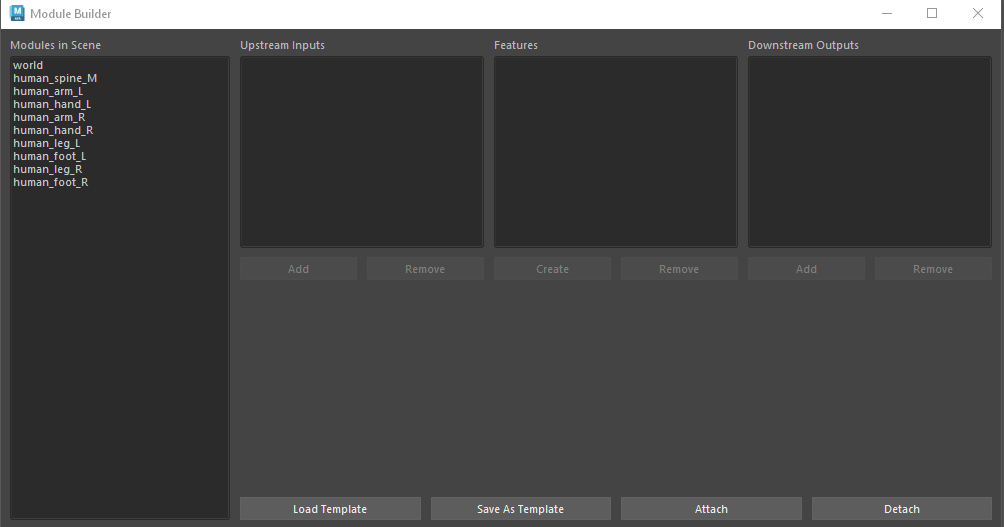

When the UI is executed in Maya, it searches the scene for joints with specific custom attributes that define them as part of my autorig system. At runtime, all subclasses of the ModuleBase class are imported and added to MODULE_REGISTRY to make a pool of modules to search for. If the joints described in the ID list property are present in the scene, they will become available in the UI for the user to add features to.

Say you would like to add a tail module to this autorig system. You would make a new .py file with a class that is a child of the moduleBase. Certain data must be added due to abstract design, which will be pinged as an error if not implemented. Once this is complete, the module is ready and fully compatible with the UI. If the correct joints were in the bind skeleton in the current scene, the Tail module would become an option in the left column.

The same goes for extending the Feature class. I don’t currently have a feature for spline IK, but this would be useful for things like Tails, Spines, and other long joint chains. This can be accomplished by making a subclass of the Feature class, and adding the logic there. Any module that wants to utilize the new spline IK would need to add a class reference to the supported_features property in that module.

File I/O and Flexibility for Artists

Although a rigging artist will likely know a decent amount of Python, having a clear UI can be convenient and easier way to get started than having to pour over proprietary documentation for a system like this.

Unlike a DCC like Houdini, Maya is lacking when it comes to bi-directional work. In a manual rig, removing an unnecessary IK from a limb would be a nightmare of editing constraints and switches, followed by testing to make sure the systems left behind still function properly. The separation of responsibility in my class design makes adding system removal functionality much more simple.

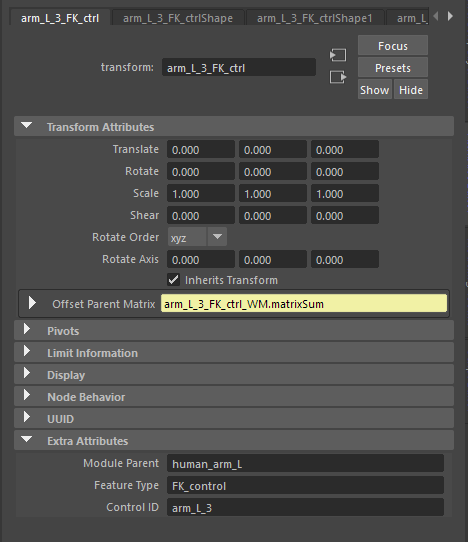

A module’s representation in Maya is a collection of organizational group nodes and a driver chain assigned the IDs defined in the module class. Adding FK would fill in the matrix constraint logic on an FK joint chain, and then parent the FK joints to the driver chain. All FK related nodes are tagged with a custom attribute to define them as such, so they can be found and deleted.

In the case of an FK/IK switch, the entire system is given input and output points in the form of locators, so removing one or the other from the switch would just require breaking the connection between the pickMatrix node and the output locator.

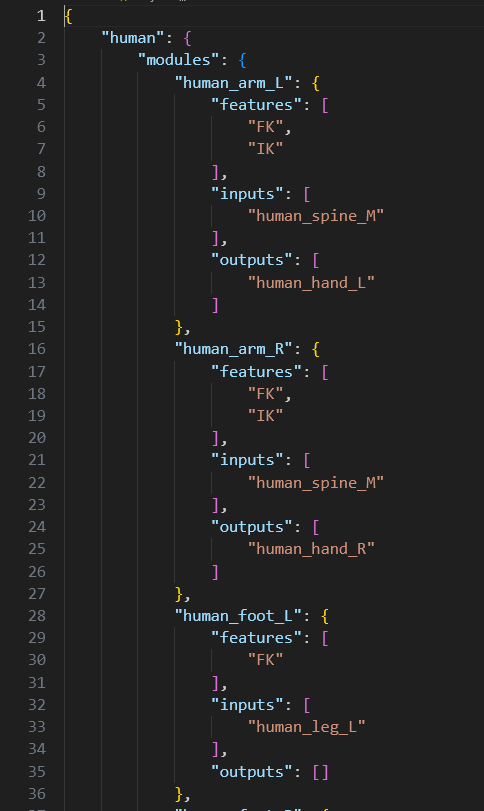

Both my Module Builder and Shape Factory employ a .json style export system to make templates for future rigs. If a user was building a human rig, and landed on an iteration that had all the basic features needed for other human characters, the module and feature instructions can be saved out to a .json. This will be interpreted and made to call the same functions that the UI did by reading the .json file.

I find the best tools are ones that are straightforward to work with for both artists and programmers. A tool is more likely to sit comfortably in a pipeline when everyone who touches it finds it approachable and easy to work with. I intend to take this philosophy into my next project, focusing on a helper tool for bind joint creations that is compatible with this modular system.